The Story of Winnetka Spirits

Categories: Gazette

Gazette Article by Becky Hurley

Appeared in the Gazette: Fall 2011

Winnetka, like much of the North Shore, has a complicated history with drinking. Although the village was officially “dry” for most of its early years, research into the distant—and not so distant—past suggests that occasionally there may indeed have been a “Big Noise” coming from Winnetka.

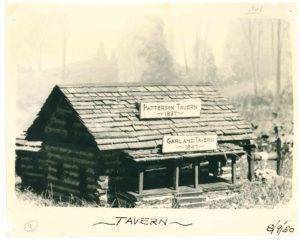

The first building in what would become Winnetka was the Patterson Tavern, established in 1836 when stagecoach service began. According to early Historical Society research, the Patterson Tavern and the Schmidt-Burnham Log House, like other wayside inns, were called “groceries” and sold liquor by the drink, leading intoxicated patrons to sometimes freeze to death traveling from tavern to tavern.

Photograph of model of Patterson Tavern (Model made by Frank Windes), from Winnetka Historical Society Collection.

But by 1869 when it was incorporated, Winnetka had reformed and put into its special village charter a prohibition against the sale of “spirituous, vinous or fermented liquors” under penalty of an enormous $50 fine. (This special charter cleverly eliminated the ability of the public to lift the prohibition by referendum.) Northwestern University also had a special charter—not only prohibiting the sale of liquor on campus but within four miles of the University. This not only kept Evanston “dry,” it also affected neighboring North Shore communities.

Several drinking spots were just outside the four-mile limit: “No Man’s Land” in Wilmette and the Village of Gross Point just west of Ridge Road. Evanston was a leader of the prohibition movement, as home to the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, founded there in 1874. Neighboring communities like Winnetka supported the idea. In 1893 the Reverend Quincy Dowd of the Winnetka Congregational Church was an Illinois delegate to the World’s Temperance Congress, and in 1908 the members of the Winnetka Women’s Club (then still over a decade from receiving the right to vote) decided to support a spring election to abolish saloons in Gross Point by “using our influence and our tongues in reminding our husbands to vote.”

Was the fight against alcohol part of a larger antipathy toward the German Catholic farmers in the area? A history of Saints Faith Hope and Charity parish, established in Winnetka in 1936, notes that “tension grew between the Protestant temperance movement centered at Northwestern University and the beer-drinking German Catholic farmers. This may have contributed to the resistance which our parish encountered when it was first started.” And of course St. Joseph parish, founded in 1845, was located squarely in Gross Point, home to as many as 15 taverns at the time alcohol was banned by a township-wide referendum in 1909. It is interesting to note that voters in Winnetka were more willing to ban alcohol in Gross Point (80.5%) than voters in other voting towns. The voters of Gross Point, of course, did not support the ban. Since taverns were the town’s sole source of municipal revenues, Gross Point went bankrupt and disappeared by 1926.

Prohibition was the law of the land from 1919 to 1933, but even after the ban on alcohol was repealed, Winnetka, as well as Evanston, Wilmette, Kenilworth and Glencoe, remained dry. When sentiments began to change in the 1970s, Evanston again led the way, obtaining a court decision allowing the sale of alcohol on Northwestern’s campus. Wilmette followed suit soon after allowing the sale of beer and wine in grocery stores and the consumption of alcohol at restaurants with dinner. Other township villages such as Winnetka passed similar ordinances beginning in the 1980s.

During our research for this article we asked a number of Winnetka residents with long memories and longer family histories to share stories of where and how Winnetkans may have in fact had a drink during the “dry” years. Most swore that they could have no way of knowing such a thing, and that anything they may be able to report was strictly word-of-mouth from other less well-behaved residents. We do have some leads (there was strong mention of No Man’s Land, Highwood, Skokie, and of course Chicago, where the Big Noise was heard). We have, however, been thwarted in our attempts to locate true-to-life speakeasies, hidden home bars, lively clubs or anything similarly exciting in Winnetka. If you have any stories, please contact us, and we will follow up with a better report of what mischievous Winnetkans (not you of course) may have been up to in those “dry” years.

I believe that Northfield was not part of the ban in the sixties. I remember going to Seuls to pick up beer with my future brother-in -law. It was in a cooler that looked like an icecream freezer. it was very small and not the sports bar and restaurant that it later became.